Today was the first day of March of the Living Australia. It was also the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom HaShoah). I have been to many Yom HaShoah ceremonies, in Melbourne, Sydney and Israel, but none compare to the extraordinary, humbling and truly emotional ceremony that we had the privilege of participating in tonight.

Today was the first day of March of the Living Australia. It was also the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom HaShoah). I have been to many Yom HaShoah ceremonies, in Melbourne, Sydney and Israel, but none compare to the extraordinary, humbling and truly emotional ceremony that we had the privilege of participating in tonight.

The ceremony came at the end of what was only our first day, yet it feels already like we have been together for so long, given how much we were able to pack into just one day. After an introductory session, we walked through the Jewish section and in one of the old synagogues, as we came in to have a look, we heard some singing. Inside we found a group of maybe 20 or so Chasidim – some from the UK and some from Israel – who were visiting Krakow to commemorate the anniversary of the passing of one of their rabbis. Whilst in the synagogue, they burst into spontaneous song and then harmonious prayer.

In a city and a quarter where so much of the Jewish revival is for show seems fake, these men (and yes, they were all men) and their singing, combined with their garb, felt like it brought some authenticity and a taste of the old world into a once thriving Jewish community. For some in our group this unplanned and unscripted moment will be a highlight of their tour.

Later at the Galicia Jewish Museum we were guided through the exhibit of 150 or so photos, by Kasia, the knowledgeable and very articulate head of education at the museum. She showed us the Galicia of old and the Galicia of today, from the old villages scattered throughout the region which used to be predominantly Jewish, to the modern Krakow Jewish festival. Most importantly, she pointed out that Krakow, Galicia and Poland in general do not have a one-sided story when it comes to the Jews and the communities that used to be here. At some point in history some of the towns were more than 60% Jewish and Poland was considered the ‘Goldene Medinah’ – a land of prosperity and richness – but then at other times it was of course the land of tragedy and destruction. Both are part of the Polish narrative, though some are sometimes too blind to see it. Part of our reason for being here, especially at this time of year, is to open our own eyes and in the process hopefully remove the shutters for others.

Then it came time for the evening ceremony. All we knew going into it was that it was going to take place inside one of the refurbished old synagogues. What we didn’t know was that we weren’t going to be the only ones there or how moving it would be. After all the usual keynote addresses, it came time for the candle lighting – six candles representing the six million Jews, like in every such ceremony. Whilst three of them were lit by three esteemed members from our group, the other three were lit by representatives of the visiting groups. One by an American who was the family representative of Ed Mosberg, a survivor who dedicated his life to Holocaust memorialisation and Jewish philanthropy; one by Jessica, a Polish non-Jewish woman who spends her life learning and teaching about the Holocaust and its impact on Poland; and one by Jonny Daniels, the inspirational founder of an organisation called From The Depths, which is dedicated to Holocaust memorialisation. As part of his work, Jonny discovered a non-Jewish family near Krakow who became the custodians of a Torah scroll when the Jewish family next door to them left it behind after they were forced out. Not knowing what to do with it, it lay dormant for over 70 years and at one point part of it became a doormat. When Jonny met them and discovered it, rather than burying it as per Jewish custom, he decided to preserve and restore and has been travelling the world looking for survivors and getting each of them to write a single letter so that each part of the restored section will be written entirely by survivors.

Then it came time for the evening ceremony. All we knew going into it was that it was going to take place inside one of the refurbished old synagogues. What we didn’t know was that we weren’t going to be the only ones there or how moving it would be. After all the usual keynote addresses, it came time for the candle lighting – six candles representing the six million Jews, like in every such ceremony. Whilst three of them were lit by three esteemed members from our group, the other three were lit by representatives of the visiting groups. One by an American who was the family representative of Ed Mosberg, a survivor who dedicated his life to Holocaust memorialisation and Jewish philanthropy; one by Jessica, a Polish non-Jewish woman who spends her life learning and teaching about the Holocaust and its impact on Poland; and one by Jonny Daniels, the inspirational founder of an organisation called From The Depths, which is dedicated to Holocaust memorialisation. As part of his work, Jonny discovered a non-Jewish family near Krakow who became the custodians of a Torah scroll when the Jewish family next door to them left it behind after they were forced out. Not knowing what to do with it, it lay dormant for over 70 years and at one point part of it became a doormat. When Jonny met them and discovered it, rather than burying it as per Jewish custom, he decided to preserve and restore and has been travelling the world looking for survivors and getting each of them to write a single letter so that each part of the restored section will be written entirely by survivors.

Without planning it in advance and knowing that within our group there was a child survivor, he asked Henry to write one of the letters with him, in a part of the ceremony that left everyone in tears. How could we not cry when we were witnessing an extraordinary act of revival in such a historic venue on the eve of such an important day?! It set the scene for what will undoubtedly be an even more emotional couple of days in Krakow and Auschwitz.

19 April

Auschwitz. For most thinking people around the world, the name alone conjures up images of death, destruction and annihilation. For the last two days, the March of the Living Australia group had the opportunity to visit Auschwitz-Birkenau, both for the march itself on Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day) and then on our own.

Coming into the site didn’t initially feel real. We entered with several hundred others, and after passing through security, we were suddenly walking along the path under the infamous ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ sign. Most of us have seen this sign in pictures for decades and have read about its meaning, but to walk under it felt surreal and almost otherworldly. In fact, the entire experience felt somewhat like that, in part because we were doing it with so many others as we were preparing to march to Birkenau. To some extent it felt a little like organised chaos, and as it got closer to the march itself, a bit like a controlled spectacle too.

While waiting for the 10,000 or more people from all over the world to enter the complex so that the march could begin, we did what our tour guide called ‘hurry up and wait’. We were ushered quite speedily to our holding space, between two of the barracks, and then for more than an hour, we waited. On one side of us was a large contingent of Argentinian Jewish students, whilst on the other side was a small group on non-Jewish Japanese Israeli lovers who come on the march each year. There was truly an international feel to the affair, made all the more so by Israeli boys from Chabad who came and offered to put Tefillin on many of the Jewish males amongst us.

Eventually, the time for the march began. What surprised me was how pedestrian it was. We left the complex of the barracks and then stepped onto a suburban street that connects the two camps. Most of the march actually was on closed-off roads with police directing traffic rather than through camps. A group of Poles lined some of the streets in support of the march, but for much of the way there was a festive atmosphere, with some groups even singing as they marched. At one point, one of the younger members of our group got separated from the rest of us, but that is because she found some members of the Los Angeles contingent who studied with her father, and they shared stories of their two families. The suppleness of Jewish geography never ceases to amaze me, and no doubt that was one of many such stories on this day where so many Jews from around the world all together in one place. In our hotel alone we often bumped into groups from Costa Rica, Venezuela, Mexico and various American states.

The march ended with a ceremony conducted mostly for the American audience, but that was certainly not the highlight for us. We actually spent most of the bus ride back criticising it. But the march was nonetheless impactful and meaningful, if only because it had such a global feel on such an important day.

The following day we came back to the same site with fewer people and less of a celebratory atmosphere. In fact, it finally felt – to me at least – poignant and somber. We did a guided tour through Auschwitz I and then, though we slightly rushed through Birkenau, we held a ceremony of our own in one of the barracks with personal stories, prayers, some appropriate songs and the lighting of the memorial candle with the recitation of a memorial prayer. No one left that site with at least a tear in their eyes.

Auschwitz-Birkenau has connotations for anyone who has ever learned anything about the Holocaust. It is the epitome of torture and a synonym for every death and concentration camp in Europe. It might feel a little touristy and almost ‘Hollywood’, as our guide said, but that doesn’t take away from its poignancy, relevance and significance. It is hard to walk past the piles of children’s shoes, luggage with address tags still on them and piles of hair, without feeling the enormity of the horror and the utter disregard for human life that happened here.

To counterbalance the experience, we finished the Krakow portion of our tour with a visit to the JCC (Jewish Community Centre), which is responsible for the revitalisation of Jewish life in Krakow. Whilst they don’t go out actively searching for Jews, they have become the one-stop-shop where people who re-discover their Jewishness after years of dormancy, come to learn and feel Jewish. After all, Jews have been part of the Polish lands since at least the 14th century. Some come for Jewish and Hebrew classes with the rabbi, whilst others come simply to have yoga classes with fellow Jews. The JCC is highly aware of its position as the closest Jewish centre to Auschwitz and conducts its work with appropriate dignity and poise.

While it is hard to count the number of Jews in Poland because so many are still scared to admit that they are Jewish, the census in Poland has shown the number of Jews doubling from around 8,000 in 2011 to close to 16,000 in 2021. The majority of those are spread across seven cities, and though Krakow only has between a few hundred and a couple of thousand Jews, it is exciting for the JCC and other organisations like it to be part of potentially one of the fastest-growing Jewish communities in the world, less than a hundred kilometers away from Auschwitz. Seeing that revitalisation allowed us to leave Krakow feeling positive despite the connotations that so many associate with the city and its proximity to Auschwitz.

22 April

Life is often about contrasts and transitions, and nowhere has this been more evident than on March of the Living. After leaving Krakow, we spent two days visiting some of the most tragic sites that many of us are ever likely to encounter. From the ruins of Majdanek, to the sombre emptiness of Treblinka, and to the utter devastation of a site in the Iopuchowo forest that saw 2,400 Jews killed in just two days. Each place was very different, but showed the brutality that humanity is capable of in very specific circumstances, and the way those atrocities are remembered.

But this trip has not only been about visiting the sites where terror occurred. In Lublin, just minutes away from the concentration camp of Majdanek, we walked through the former Jewish ghetto and then visited what is left of the Hevra Nosim synagogue – the only one remaining in town. Rather than function as a working shule, the room consists of the artefacts that once graced the synagogue, along with many other Jewish items, all of which were lovingly collected, looked after and strategically placed by Pavel, one of the last remaining Jews in town. In contrast to what we saw on the outskirts of his city, it was so special for us to meet such a remarkable and passionate man, who has essentially dedicated his life to the physical restoration of his city, even though he is well aware that there is unlikely to be a thriving community in Lublin ever again.

The greatest contrast however, for so many of us, was Shabbat. Though the sabbath is inherently about turning off, resting and doing things a bit differently, this Shabbat in Warsaw was about all those things and more. For those of us who went to the synagogue on Shabbat morning – the one remaining synagogue of the nearly 400 that used to be in Warsaw – we saw a shule that was heaving and joyous with March of the Living delegations from all over the world making up the vast majority of the congregation. Without us there might only be 50 or so congregants on a regular week, but when the March is in town, which it hasn’t been since 2019, the synagogue and the Jewish community of Warsaw grows tenfold. The locals embrace it, the rabbi plays up to it and the result was a Shabbat filled with liveliness and the revitalisation of Jewish life in all its forms, even if only for one Shabbat, though even with a small number of regulars, the shule is always active and full of life.

Contrast though is not only about going from dark to light. It is also about dealing with emotions and thinking about the future. On Shabbat afternoon, as an Australian group, we had three remarkable presentations, each with a different focus. The first was by a couple who run the only Judaica store in all of Poland. Pre-war, with such a large Jewish community, Poland had tens if not hundreds of local artists and Jewish craft makers. Today there is just one – MiPolin (Hebrew for ‘From Poland’) – and they not only make jewelry, Seder plates and candle holders. Their main products are recreated Mezuzahs. Several years ago they began going on trips all over the country, finding the traces of Mezuzahs in doorposts, and casting those traces in bronze. It was a passion project that was supposed to be for an exhibition but has become a labour of love that has now produced casts from 160 different towns all over the country. And the remarkable part is not even the mezuzah itself – each of which is beautiful – but the research and the story they do about each home, each family and each town. While they know as much as anyone that most of these towns will never have thriving communities again, these stories bring life back to the towns and the mezuzah provide a tangibility to those stories.

The second presentation was by a nearly 92-year-old former Polish serviceman who is also considered one of the 27,000+ righteous among the nations recognised by Yad Vashem, and one of only 108 who are still alive, with over half in Poland. As a 12-year-old he had a best friend on his street who was Jewish. When the war began he and his family brought the boy into their family under the direction of his mother, and raised him as one of their own till the end of the war. All survived, and when the Jewish boy, now a man, died in 1989, he left 33 descendants, all because of the efforts of one non-Jewish family. When he was going to be honoured by Yad Vashem, they said only living people are to be honoured, but his righteousness continued to shine through and he refused to accept the honour unless his mother was to be honoured too. Now they both have a place at Yad Vashem, and the Jewish family, now in Israel, always hold an empty seat at their family table for these two remarkable people.

The final presentation was by a representative from Forum for Dialogue, an organisation that essentially teaches the non-Jewish residents of Polish towns about the Jewish histories of their own towns, most of which were lost not just because of the war, but because of 40 years of Communism that came immediately after it.

Taken together, these three presentations put into sharp perspective what we have seen and learned this week. That the war ruined and decimated this country and drove most of the Jews away, but this country had a thousand years of active Jewish life beforehand, and now there are people and organisations determined to show to all of us what was here before. Hearing this, seeing this and living it this week gives us all hope.

23 April

Jews first arrived in Australia with the white settlers and have built up the community over the decades and centuries to make it one of the most vibrant and thriving communities in the world. Though our numbers are small, our impact is great and has been all the more strengthened by so many Holocaust survivors who came to our shores in the late 1940s and into the 1950s. Today we saw what they left behind.

On a non-descript street a couple of blocks away from the only remaining synagogue in Warsaw, there is a square with park benches, some street art, a concrete clearing and some lovely trees. Though it was Sunday, there were people around walking their prams and their dogs, and if it were a weekday, the square would be filled with ordinary Poles drinking their lattes from one of the many trendy coffee shops in the area. But a century ago this very square was one of the most Jewish gathering spots in town, not unlike Carlisle Street in Melbourne or Hall Street in Sydney. In fact, for over a thousand years Poland was one of the most prominent countries in the world for Jews, and Warsaw was close to a third Jewish. Then in the blink of a Holocaust eye, 90% of the Jews of Poland were slaughtered and most of the rest fled.

Many of those who died dignified deaths before the war, or who stayed and died in the intervening decades, are buried at the cemetery at Okopowa Street, the largest Jewish cemetery in the world outside of Israel. In just a few blocks it tells the story of the history of a lost community. As such, this cemetery more than many others I have been to, lives up to one of the Hebrew names for a cemetery – Beit HaChaim (a place for the living). Though their lives have ended, the stories they tell bring the community back to life.

But nothing really brings a community back to life like a vivid museum, and Polin is one of the best museums in the world, having won numerous awards since it opened a decade ago. Built-in the heart of the former Jewish ghetto on the site gifted to the museum by the state, the museum tells the full story of the Jews of Poland and how they thrived in this country for so long before the war. At one point there were over a thousand little shtetls spread across the entire breadth and length of the country, each with its own community of Jews. It wasn’t all roses, and the museum doesn’t shy away from challenges but handles each era with grace and a well-crafted story, replete with décor and a design to match the era. A two-hour visit was never going to be enough, but it was sufficient to whet the appetite and show that although there is very good reason why there are so few Jews left in Poland, there is also a long history that Poles and the decedents of the former residents can be duly proud of.

Poland for us and undoubtedly for all the March of the Living delegations that descended on this country this week, was a country of mixed and sometimes contradictory emotions and sites. On the one hand, Warsaw is a rocking city and one of the most modern I have seen, despite a few remnants of its Communist and pre-war past. Parts of the old city look like they wouldn’t be out of place in the vibrancy of Amsterdam, whilst the area around the palace could easily double for Paris, such is its unexpected beauty and charm. Yet in amongst all that, there are constant reminders of the city’s recent past and what was lost. On the sides of some buildings, if one looks closely enough, there are plaques with descriptions about what was once housed in those buildings, and in other places there are memorials, recreations or even surviving remnants.

In other parts of the country, like in Majdanek for instance, the concentration camp shares an almost transparent fence with backyards of people’s homes. As we walked through, in at least two of the yards we could see kids playing, seemingly oblivious to what was on the other side of their fence. It perturbed most of us to no end, but for them it is entirely normal. Yet even where there are no fences or plaques, it is still difficult to forget that just hours from the major cities are the sites of so many concentration and death camps, including some of the most iconic ones.

In many ways it is possible to argue that the Holocaust happened in Poland or to Poland, but that only tells half the story. So much of it happened here because so many of the world’s Jews were based here. The goal of the Nazis was to wipe out all of the Jews no matter where they were, and Poland just happened to have the highest concentration of Jews at that time because for a thousand years it was their home. For centuries Jews felt safe and comfortable in Poland and could never have imagined that one day their communities would be decimated, in much the same way that we can’t imagine a similar thing happening to our communities in our day. But the truth is that it could happen.

In many ways it is possible to argue that the Holocaust happened in Poland or to Poland, but that only tells half the story. So much of it happened here because so many of the world’s Jews were based here. The goal of the Nazis was to wipe out all of the Jews no matter where they were, and Poland just happened to have the highest concentration of Jews at that time because for a thousand years it was their home. For centuries Jews felt safe and comfortable in Poland and could never have imagined that one day their communities would be decimated, in much the same way that we can’t imagine a similar thing happening to our communities in our day. But the truth is that it could happen.

We have genuine hope that the world has learned from the lessons of the past, but we also know that that is not quite true. In fact, that is the reason why March of the Living was created in the first place, and why it is still so relevant today. We truly have seen what we can’t learn just by reading history books, and now, as we are about to embark on the second part of our encounter in Israel, the juxtapositions of this trip will likely become even greater.

26 April

Coming into this program, we knew we would be in Israel for Yom HaZikaron and Yom HaAtzmaut (Days of Remembrance and Independence), but we didn’t know what they would be like or how they would make us feel. After a week in Poland at some of the most terribly sad and nihilistic places in the world, we needed a change of mood, and almost from the first moment in Israel, that change began to occur.

We flew to Israel from Warsaw on a charter flight with March of the Living delegations from across the world, and arrived at almost the same time as a few other flights. The atmosphere at Ben Gurion airport therefore was festive and chaotic from the start, and even a lack of sleep couldn’t dampen our spirits. To understand the complexities of this land, we began our time in Israel at Tel Aviv University’s ANU Museum, which is an interactive and very technologically advanced exhibition space about the Jewish people and many of their stories. We then drove to a kibbutz and joined the locals for their somber but very poignant ceremony to commemorate Yom HaZikaron. Unlike similar such ceremonies at home, there were no speeches by dignitaries or anything extraneous; just a few readings, appropriate musical pieces and stories about the fallen, along with the recitation of a prayer and the lighting of a memorial candle. We were then privileged to meet some of the soldiers from the kibbutz and heard some of their stories.

We flew to Israel from Warsaw on a charter flight with March of the Living delegations from across the world, and arrived at almost the same time as a few other flights. The atmosphere at Ben Gurion airport therefore was festive and chaotic from the start, and even a lack of sleep couldn’t dampen our spirits. To understand the complexities of this land, we began our time in Israel at Tel Aviv University’s ANU Museum, which is an interactive and very technologically advanced exhibition space about the Jewish people and many of their stories. We then drove to a kibbutz and joined the locals for their somber but very poignant ceremony to commemorate Yom HaZikaron. Unlike similar such ceremonies at home, there were no speeches by dignitaries or anything extraneous; just a few readings, appropriate musical pieces and stories about the fallen, along with the recitation of a prayer and the lighting of a memorial candle. We were then privileged to meet some of the soldiers from the kibbutz and heard some of their stories.

During the day on Yom HaZikaron, we visited Caesarea, the Atlit detention camp, a Druze village and then Nirim, an educational organisation for at-risk youths. We then followed this up with an Anzac Day ceremony, and though it wasn’t at dawn, the location on the banks of the Mediterranean just south of Haifa was very picturesque and memorable. The day was not entirely about remembrance, but finishing with an Anzac service made the entire day much more relatable and meaningful for our Aussie group.

Back in Tel Aviv, as soon as the sun set the atmosphere changed. Israel is probably the only country in the world that has its independence day immediately preceded by its remembrance day, but the change of mood is palpable and all-encompassing. From the electronic billboards proclaiming independence, to the cacophony of noises on the streets, it definitely felt like the city and the country was ready to party. Even though we split up and enjoyed the town in small groups, each of us found a party, some music or the right kind of atmosphere to enjoy the night.

The following morning we headed to Jerusalem for the first time, and started at the Tayelet, a site that has seen tour groups come for as long as any of us can remember. It is one of the few places in town that allows for almost uninterrupted views of the old city, west Jerusalem, the Silwan valley, much of the east of the city and all the way to Jordan. We then joined thousands of other people from various March of the Living delegations for a concert ahead of a march into the old city, culminating at the Western Wall. The atmosphere was entirely festive, with drummers, music blaring throughout the route, and lots of spontaneous singing. A couple of hours later we all gathered again at Latrun for a concert to mark both the official end of March of the Living for some delegations, and Yom HaAtzamaut. It felt a little like the closing ceremony of a sporting event crossed with Eurovision, and in fact Netta – the Israeli winner of Eurovision from 2018 – performed at the concert, along with a host of other singers. A highlight for many of us was seeing an Israel-loving Japanese choir perform a medley of Hebrew songs. Just a week earlier they waited next to us ahead of the march in Auschwitz, and it was almost hard for many of us to reconcile that the two things happened just one week apart.

The truth is that the dichotomy of the story between dark and light is one that so many of us are struggling with, but equally, is one of the things most of us will take away from this experience. Though the actual March of the Living was only one week ago, it feels like it was ages ago or certainly on another trip. The fact that the concentration camps of Poland and the festivities for Israel’s Independence Day can occur in the same world is mind-boggling, but even more so that the people who escaped the clutches of the Holocaust were the ones who were the original pioneers of this land. Of course there are many complexities and competing narratives in Israel, and we will be exploring these over the next few days including during Shabbat in Jerusalem, but for now, the mood is joyous and exhilarating.

28 April

With the days of significance over, both the program and the participants in it were able to see Israel in a different light. We began that different light with a visit to the Begin Centre, an institution dedicated to telling the story of Israel’s first conservative Prime Minister. Unlike some of the other museums we have seen, it wasn’t quite as technologically advanced, but more importantly, it felt to most of us that it dived too deep into the life of someone most of us knew very little about. And whilst a deep dive is good, we may have needed some more context before the visit. Unfortunately, that set the tone for some of the intensity that we have felt ever since.

The visit to the Begin Centre was followed immediately by a talk by Rabbi David Rosen, Israel’s pre-eminent interfaith spokesperson, and one of the most erudite and articulate speakers on the topic of understanding the other. In a country as polarised and chaotic as this one, hearing someone so in tune with the politics but so involved with the efforts to understand difference inspired all of us and made us wish that there were more hours in each day. Each of us could have easily spent an hour with him on our own and that still would not have been enough. We needed to finish with him because we had a tour of Yad Vashem to get to. And whilst some of us weren’t even sure why we needed to go to Israel’s Holocaust museum after a week in Poland, it was actually a surprisingly life-affirming visit. Not only is the museum set amongst a beautiful forest with a view, it tells the story of the Holocaust with empathy, meaning and compassion. For two people in our group it was even more meaningful. One found an artefact that belonged to a family member, whilst another discovered that his uncle was in one of the pictures on display. After a week at many of the sites where the images came from, the museum had a new and impactful meaning for us.

We then changed tack again and had two interesting and intense presentations, both of which were triggering for some of the people in our group. The first was from an organisation called Kids 4 Peace, which brings together Jewish, Christian and Muslim kids in Jerusalem in a kind of youth movement where they play fun, educational games in order to discuss the conflict of the region, but in a way that makes sense to them. We heard from Ittay Flescher, the Australian educational director of the program, that for many of these kids, this is their only opportunity to seriously interact with these issues. It is a small grassroots organisation that only has an annual intake of 80 kids, but is one of 300 organisations in the country that is trying – at least on some level – to bring people

together so that they see there are multiple sides to a story, and so that ultimately a peaceful solution can be found.

To that end, our final speaker for that day was Ahmed Mona, the son of Palestinian bookshop owners, who came to talk to us about ‘the Palestinian perspective’. But as we quickly discovered, much like there is no unified Jewish view on anything, there is equally no monolithic Palestinian perspective. Ahmed presented an idea that he even admitted does not have mainstream support, but it was nonetheless important and interesting for many of us to hear his viewpoint and to discuss the issues with him in a respectful and comfortable environment, even if it did raise within tensions amongst some of us.

We continued the discussion at Ammunition Hill the following morning, but as an antidote to all the talking and thinking, our last stop before Shabbat was Machne Yehuda market in central Jerusalem, and a walk through the streets. No other place in the world compares to the chaos, bedlam and utter havoc of the market on a Friday afternoon, yet somehow it all works and everyone comes out with what they need. Within an hour the noise died down and now we are ready to spend another Shabbat together, this time in Jerusalem amongst all the noise and chaos, and for many of us, nothing could be more beautiful.

30 April

There is a certain unique quality about Israel that has an affect on everyone who visits, whether they are first-time visitors or seasoned travellers to this land. That quality is hard to describe but was demonstrated in our group on Friday night when we all went down to the Kotel (Western Wall) for Shabbat services.

Later at dinner, when we relayed the story of what happened to one or two non-Jews at the table, their overriding sense was that the Jewish people have an unrivalled sense of community, and it is this sense that is so unique and so much more evident in Israel. We saw it on display for the entire fortnight, but especially during our week in Israel and particularly on the last evening.

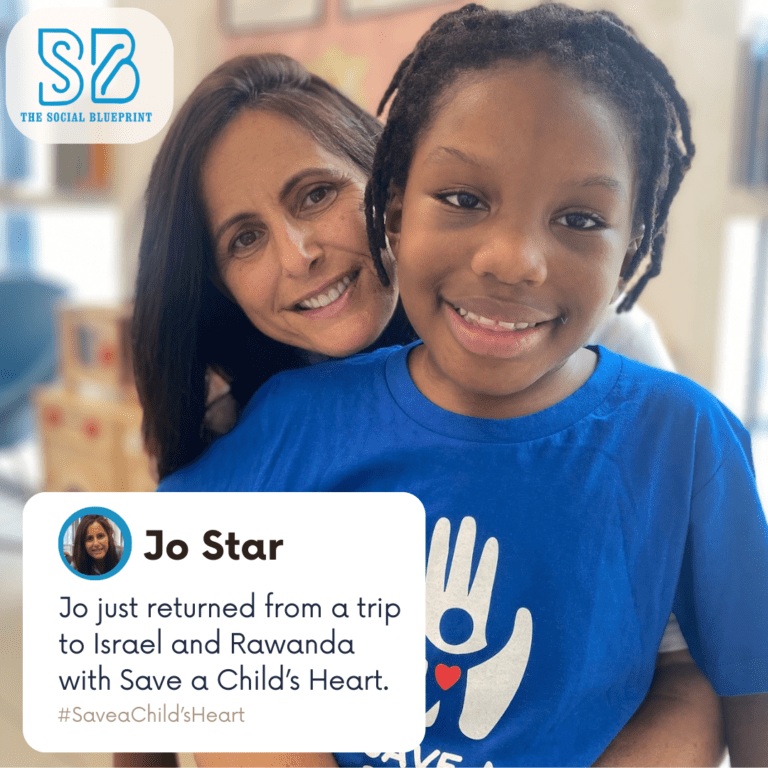

After a rainy Shabbat walk and inspiring afternoon talks, we began our last day together with a visit to the Save Our Child’s Heart house in Holon near Tel Aviv. The organisation trains cardiologists from a number of countries, and brings young heart patients to Israel for critical heart surgeries from countries that don’t yet have specialist surgeons. Their care for their patients, irrespective of religion, country or status was truly inspiring and showed how connected we all are at a human level.

We then visited the Aiel Sharon Park, an environmental reserve four times the size of Central Park in New York, and built literally on what was once Israel’s largest rubbish dump. It now looks pristine and immaculate, and shows what can be achieved with vision and care for the community at large. From what was once a dangerous eyesore to this beautiful oasis, the transformation has been amazing.

Then after a visit to the Rabin Museum, which traced not only the life of Prime Minister Yithak Rabin but also the life of the State of Israel from its founding to the late 90s, we ended the program with a farewell dinner, where the community spirit was as strong as ever. Each participant in their own way praised the program, but more importantly, praised the people that they shared the adventure with. We participated in a program together, but left the experience with a community of like-minded adventurers who have now experienced Poland and Israel in one of the most unique ways that anyone will ever do. Even for the majority of us who had been to Israel before, this was not the average Israel trip. It was one filled with difficult conversations, visits to unique sites, meetings with diverse groups and leaders, and a deep self-reflection that has only just begun.

Then after a visit to the Rabin Museum, which traced not only the life of Prime Minister Yithak Rabin but also the life of the State of Israel from its founding to the late 90s, we ended the program with a farewell dinner, where the community spirit was as strong as ever. Each participant in their own way praised the program, but more importantly, praised the people that they shared the adventure with. We participated in a program together, but left the experience with a community of like-minded adventurers who have now experienced Poland and Israel in one of the most unique ways that anyone will ever do. Even for the majority of us who had been to Israel before, this was not the average Israel trip. It was one filled with difficult conversations, visits to unique sites, meetings with diverse groups and leaders, and a deep self-reflection that has only just begun.

The Bar Mitzvah at the Kotel was just one highlight in a trip that was no doubt filled with many, though each of us will surely have different highlights. But what I know for sure, and what will certainly be true for all, is that we built a unique community together and one that is sure to stick around long after we come back home to our normal lives and this experience becomes just another memory, but hopefully not a faded one.

Author: Alex Kats, Co-President of March of The Living, first-time participant on the program. His personal observations and emotions.

Author: Alex Kats, Co-President of March of The Living, first-time participant on the program. His personal observations and emotions.