When do we remember the Holocaust?

For many of us, the answer is always.

At the Melbourne Holocaust Museum, we find ourselves perpetually remembering the Holocaust. Moreso, we are also always finding ways to preserve and transmit the testimonies of our survivors so that future generations might be able to engage meaningfully with the subject. For student and adult visitors, therefore, a visit to our museum marks an opportunity to remember the Holocaust.

For most members of the public, who do not live with thoughts of the Holocaust, the calendar provides two key moments on which to pause and to reflect. On the 27th of January every year, we commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day (IHRD). Then, on the 27th of Nisan, we commemorate Yom HaDhoah.

Aside from both dates happening to fall on the 27th of their respective months, they have little else in common, and they both entered the popular consciousness by a curious route.

The history of Yom HaShoah: how did Nisan 27 become a day of Holocaust Remembrance?

The first commemoration of Yom HaShoah took place in 1951 – almost sixty years before the first commemoration of IHRD. Controversial from the outset, it represented the Israeli government’s compromise position on a long-standing debate that concerned how we should memorialise the Holocaust.

Many religious Jews (including the Israeli rabbinate) felt that dates already existed to commemorate such tragedies. The 9th day of the month of Av, for example, is a day of grief and mourning. Ostensibly, that grief is for the destruction of the two temples, but there is a long history of its being co-opted as a day of mourning later calamities. Similarly, the 10th day of the month of Tevet is a fast day that has long served as a day of mourning for those whose dates of death are unknown.

For many other Jews, these dates are insufficient. The Holocaust is both too recent and too large. Unprecedented in scope, it makes earlier tragedies that befell the Jewish people almost comically insignificant. A destruction of the enormity of the Holocaust cannot simply be grafted onto an already existing date but requires a new date for its commemoration. But when?

The full name of this commemoration was not Yom HaShoah but Yom Hazikaron LaShoah Velagevurah: The Day of Remembrance for the Holocaust and for the Resistance. In choosing a date, proponents of this idea sought one that would coincide with the most famous of armed uprisings – the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of 1943.

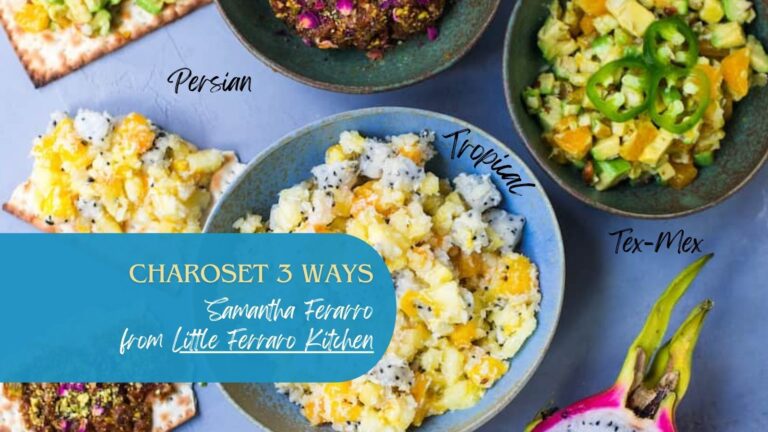

As detractors were quick to point out, the problem with this is that the Warsaw Ghetto uprising coincided with Pesach. The Hebrew month of Nisan – and the festival of Pesach in particular – represents a period of liberation and salvation in Jewish history and one on which it is forbidden to fast. As a result, and by way of a compromise, the Israeli Knesset selected a date after Pesach and one that – still in the month of Nisan – would not be a day of fasting.

As a result, the 27th of Nisan became a day of memorialisation for the Holocaust. In Israel, cinemas are closed, and Israeli television broadcasts Holocaust-related films and documentaries. When a siren sounds in the morning, traffic comes to a standstill and – across the country – people observe two minutes of silence.

IHRD, on the other hand, is not marked by any such regulation of activity. Established by the UN in 2008, the chosen date reflected the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau by Soviet troops. As Auschwitz has become emblematic of the camp system as a whole, and therefore representative of the Holocaust in the popular imagination, its liberation marks an occasion for solemn commemoration and reflection. This too, of course, is controversial. Most Holocaust survivors were not in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Significant numbers of people survived because they avoided deportation and were therefore not in the camp system at all. Through flight and hiding, they endured fear and deprivation, discrimination and terror. As horrifying as their experiences were, many did not consider themselves Holocaust survivors after the war since the initial understanding of the Holocaust was synonymous with the camps. At the Melbourne Holocaust Museum, we know that all who endured Nazi terror, whether they left Germany and Austria before the outbreak of the war or whether they survived the war years by concealing their location or identity, are survivors of the Holocaust. On IHRD, every year, we pay our respects to them all. But on Yom HaShoah, we do more than pay our respects: we join them in grief. Yom HaShoah, as a counterpart to other days of mourning in the Hebrew calendar, is for more than reflection. Yom HaShoah is a time to pause and grieve, consider what was lost, and allow ourselves the opportunity to immerse ourselves in thoughts of destruction. The opportunity to do so, as all such opportunities, is altogether brief. The rest of the year is for building. By Dr Simon Holloway | Head of Education | Jewish Holocaust Centre

What is the meaning behind International Holocaust Remembrance Day?

What does Yom HaShoah mean to us?

Author