In summary

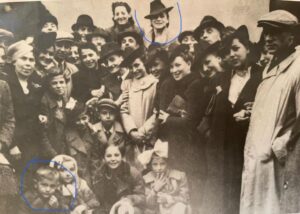

My father Fiewel Klocman came from Lodz and was married pre-war with an eight-year-old son. He was the sole survivor of 9 siblings, all married with children. They were in the Lodz ghetto, then Auschwitz and on a forced march out of there, of which 6 survived out of 10,000, to Friedland from where he was liberated. My father and his brothers were beaten many times by the Kripo because the family had been in the jewellery business and the Germans wanted to know who had purchased diamonds etc. They never gave anyone up.

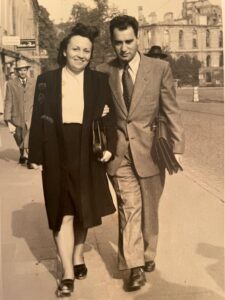

My mother Jafa Klocman (nee Grynstajn) came from Krasnystawa, was also married prewar and had a 2 year old son. She managed to jump out of a train going to Majdanek, broke into her grandfather’s office (he was a lawyer, died in 1939) and stole a birth certificate of a polish woman in his files and then applied to be a Polish worker in Germany, which is how she survived. After the war my mother organised a transport train for Jews to return to Poland and was known as the angel.

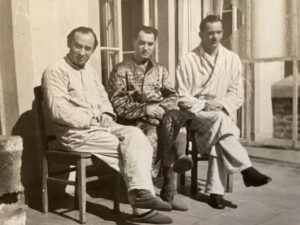

I was born in 1947 in Stuttgart and when I was a year old my father was sent to a sanatorium in the Black Forest as he had developed TB due to his concentration camp experiences. He was one of the lucky ones they used an experimental drug called streptomycin on him (it later became the cure for TB) which sent some mad, others died, he survived and was cured. After a year he returned to my mother and me and my parents decided that they had to get as far away from Europe as they could. They applied for visas to to USA and Australia and luckily the Australian visa came through first, which they accepted. The USA visa did come through later but they had already accepted the Australian one. We came in a ship called the Cyrenia from Genoa in January 1952. I turned four on the ship.

My parents moved into rooms in a house that belonged to a Jewish family called Bender (which they had rented from Germany) in Glenhuntly Road so we never got to live in the Jewish areas, which at the time was in Carlton and Brunswick, and got work in two different clothing factories although neither of them came from the trade. My father prewar was in the diamond trade (a family business) and my mother was a graduate student. Once they had learnt enough they bought a making up business which they developed into a major fashion firm called Jafa of Melbourne and at its peak employed 90 workers.

My memories

I remember very little of the journey to Australia, I recall looking at the sunset on the horizon with other children and saying there’s Australia, and of course as the ship was full of migrating families mostly Jewish there were lots of kids to play with. These families all bonded and were known as shifsbrider and shifsshwester ever after. When we arrived in Australia I remember that at what must have been customs they went through our luggage and the officers started to bounce a ball I had then slashed it open with a knife. I cried. At the house in Glenhuntly Rd there were three kids, a girl and two boys and we used to play in the sandpit in the backyard. My parents meanwhile used to bring work home, childrens overalls, that my mother had to iron for the factory she was employed at. I started kindergarten at Sholem Aleichem which was just down the road. The headmistress was absolutely horrified that that this Jewish child only spoke German and insisted that my parents speak to me in Yiddish. The changeover wasn’t that difficult.

When my parents bought the factory which was in Malvern Road there was accomodation upstairs, so we moved to Prahran and lived above the factory. In those days all of Malvern Rd from Surrey Rd to Chapel St consisted of Jewish factories, and I started school from there, Hawksburn State School, which is now Leonard Joel Auction house. It was there that our name was changed. My father tried to explain that in Polish the c is pronounced tz but of course in the 50’s this was not understood, so outside the community we were known as Klocman.

Every weekend we used to visit friends made on the boat and also friends of my dad’s that were in the ghetto with him, namely the Kupfermince family (who became Cooper) and there the discussion was always about ghetto experiences. I was too young to understand that it was their near past they were talking about.

We used to go on holidays to Hepburn Springs to a guesthouse called Beersheba which was kosher and again was full of survivors.

My parents became involved in community life very early and my father was on the Lodzger Landsmanshaft committee, I have an invitation to the Exhibition Hall for a Yom Ha’azmaut dinner with Moshe Sharett, which names my parents as committee members in 1954.

As an only child I went everywhere with my parents as they were overprotective and would never leave me home alone. I wasn’t allowed to have a bike (too dangerous) and I recall on one occasion being present when a woman started screaming and yelling, pointing at a man she recognised had been a kappo. All hell broke loose.

The Holocaust was never far away. I remember on one occasion just after my son was born my father called him by my brothers name. It was then that I realised how much had been internalised.

When my son was having his bar mitzvah we went to a factory to buy my mother a suit. When we went in the owner, Jacob Rosenberg, took one look at my father and said: “because of you I got beaten”. My father looked at him and said “what?”. He replied “don’t you remember when you tried to commit suicide and threw yourself under a truck”. Apparently the truck wouldn’t start, no matter how hard Jacob (who was the driver) tried, and it was only after they pulled my father out that it started and that was why he was beaten.

Growing up

My parents, as I’ve mentioned were very overprotective, having lost children. I was precious, treasured, but never indulged. I grew up in the factory and became a voracious reader, lying under the cutting table amongst the rolls of fabric, with my books.

When I started Mount Scopus in grade five things changed. We had moved to a house in Caulfield and I became a latch key kid and as they became more successful. We had live-in help.

The Holocaust

My father continually told holocaust stories all his life, so much so that I tuned out. My mother, on the other hand, only spoke about her childhood and not her holocaust experiences until very late in her life. It is only as I’ve gotten older that I have realised how incredible they were, having lost all their families, survived what they went through, came to a new country with no language and built a successful new life, without the help of psychiatrists and others. They just got on with it. They were also supreme optimists and taught me that there is a solution to every problem. You just have to find it. It has been at the most difficult times in my life that their experiences have sustained me and got me through. They taught me to be charitable, a love for Israel, never to be ashamed of being Jewish, that money comes and goes but who you are is what is important. The only thing of true value is a good name.

Author: Sara Gold – mother | grandmother | lawyer | philanthropist| community leader