In 2016 I decided to dedicate the 80,000 hours of my career to having a positive impact on the world. It sounds very charitable, but at its core, it was a self-interested decision which best served me. The thinking that went into this decision, and my career to date, was all triggered by the first paragraph of a fateful book that changed the course of my life:

On your way to work, you pass a small pond. On hot days, children sometimes play in the pond, which is only about knee-deep. The weather’s cool today, though, and the hour is early, so you are surprised to see a child splashing about in the pond. As you get closer, you see that it is a very young child, just a toddler, who is flailing about, unable to stay upright or walk out of the pond. You look for the parents or babysitter, but there is no one else around. The child is unable to keep her head above the water for more than a few seconds at a time. If you don’t wade in and pull her out, she seems likely to drown. Wading in is easy and safe, but you will ruin the new shoes you bought only a few days ago, and get your suit wet and muddy. By the time you hand the child over to someone responsible for her, and change your clothes, you’ll be late for work. What should you do?

My guess is that any sane person would come to the same answer. Save the child. Obviously.

This passage is from Peter Singer’s ‘The Life You Can Save’, where he goes on to highlight that hundreds of children die every day from conditions that are preventable with a relatively small donation. For many of us, such a donation might be an inconvenience comparable to, say, ruining a new pair of shoes and being late for work. So why would so many jump in the pond to save the toddler, but so few donate to buy a mosquito net and save a child from dying from malaria?

The thought experiment is confronting and perhaps isn’t intended to be taken literally. But even so, once you see the conflict between your intentions and your actions, you can’t unsee it. This paragraph set me on a path to investigate the moral obligation we have to the world, and would change my world in the process.

I read this book as I was finishing university and beginning to think about my career. It led me to the ‘Effective Altruism’ movement, and ultimately, to discover 80,000 Hours – an organisation that helps people work out how they could use their career to help others, and more importantly, why they should. The average person has 80,000 hours in their career, and I had all 80,000 hours of mine ahead of me. Spending a few hours reading what they had to say seemed wise.

I was rocked by the shallow pond thought experiment, but, I was still self-interested. More than anything, I wanted a career that I would be passionate about, I would be good at, and of course, would make me lots of money.

But after learning more about 80,000 Hours’ works, no matter how selfishly I considered my career, I always seemed to arrive at an altruistic conclusion. The career that would give me the maximum life satisfaction would be one which had a positive impact on the world. Learning more uncovered three insights that convinced me that this was undoubtedly the best path:

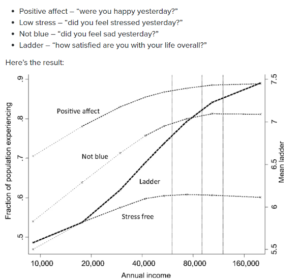

- Income reaches a point of diminishing returns for life satisfaction far earlier than you’d expect. Basically, we shouldn’t worry about making money after a point (the graph below shows how happiness metrics plateau even when income on the x-axis DOUBLES).

Source: High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being, https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1011492107

- Following your passion isn’t always possible or fulfilling. Even if you’re lucky enough to know exactly what your passion is AND for it to be realistic to earn an income from it, it’s statistically very likely your passion will change frequently, so creating a long-term career plan around it can be problematic.

- Helping others will always be fulfilling which makes a strong case for planning your career around social impact. There’s plenty of research on this, now backed up by my own personal experience.

These insights built a solid case for a career dedicated to social impact, both in terms of my life satisfaction, and moral obligation to the world. It’s given me the resolve to take risks in my career and start Anika Legal, an innovative non-profit social enterprise that provides free legal support to people locked out of the justice system.

I’m still in the early stages of my career so the jury is still out on whether the decision to pursue a career in social impact is a good one. I’ve been both applauded and scoffed at when I’ve told others I’m prioritising impact over making money. It’s felt like a fantastic decision thus far, even during the first year of starting Anika when I didn’t receive a salary. That being said, it’s early days and I’m intrigued by how the decision will serve me as I get older and my life changes.

The decision and my role as CEO of Anika Legal have given me invaluable opportunities and skills, and a passion for using social enterprise and technology to scale social impact. I’ve also had the privilege of waking up excited to go to work every day for the past five years. I’m confident that my selfish career decision will hold me in good stead for the 70,000 hours I have left.

Author

Noel Lim is the founding CEO of Anika Legal – a legal-tech non-profit that provides free legal support to vulnerable Australians who are locked out of the justice system. This free legal support is provided through an innovative service model supported by law students supervised by lawyers, and funded by universities.

Noel has led Anika Legal to numerous awards including successive AFR Client Choice Awards for Startup of the Year (2019, 2020), and was shortlisted for the 2023 Victorian Young Australian of the Year award.